Catalogue Text – ‘Living Archive: Landscape and the Rural Imagination’, The Way That We Went (Ballinglen Arts Foundation, 2021)

Living Archive: Landscape and The Rural Imagination

Joanne Laws

The long summer days spent in the Limestone Plain, where the gentle undulations of the ground only occasionally hid the distant rim of brown and blue hills; the marshy meadows, heavy with the scent of flowers; the great brown bogs, where the curlews alone relieved the loneliness… the savage cliffs of the Mayo coast; the flower-filled sand-dunes which fringe the Irish Sea.. all have left memories that can never be effaced.[i]

– Robert Lloyd Praeger, 1901

Situated in the coastal village of Ballycastle at the edge of the Mayo Gaeltacht, The Ballinglen Arts Foundation was established in 1992 by Philadelphia-based art dealers, Margo Dolan and Peter Maxwell. The couple sought to develop a vibrant residency model that would attract international artists to live and work in the region, with the additional aim of offsetting some of the tangible effects of rural decline. Over the course of three decades, Ballinglen has become a thriving artist’s retreat and an essential part of County Mayo’s visual art infrastructure, which continues to expand in scope and ambition.

To date, highly competitive residential fellowships have been awarded to hundreds of established and emerging artists of recognised ability, working across various media – from painting and drawing, to photography, printmaking and sculpture. Like other residencies, Ballinglen temporally liberates artists from their habitual or familiar environments, offering opportunities to respond to new vistas while nurturing particular aspects of their ongoing practice. Likewise, resident artists may bring with them intrinsic knowledge of distant landscapes – an intensity of prior engagement that may be temporarily transferred onto the topography of Ballycastle, when they come to stay for short periods of time.

The enigmatic and ancient surroundings of Ballinglen continue to enchant and inspire new and returning artists. Its Atlantic boundary is dramatically fringed by a serrated cliff face of primitive limestone and metamorphic rock, while its coastal moors form part of a wild ecology of blanket bog, characterised by treeless hills, colourful mosses, heathers and lichens. To the northwest are The Céide Fields – the archaeological site of an enclosed Neolithic settlement, believed to be the oldest known field systems in the world. Built by settlers five and a half thousand years ago, the site was perfectly preserved through its subsumption by an encroaching bog – an occurrence which lead archaeologist, Seamus Caulfield,[ii] likened to a “slow-motion Pompeii”.[iii] In his 1975 poem, Belderg, Seamus Heaney referred to the site as “a landscape fossilised”[iv], retelling how excavators “stripped off blanket bog”, and the “soft-piles centuries fell open like a glib”.[v]

To paint or otherwise document the land ultimately involves a one-to-one encounter between an artist and the terrain – something the late cartographer, Tim Robinson, described as “an existential project of knowing a place”.[vi] Prior to the advent of analogue photography, changes in the landscape were recorded solely through the kindred disciplines of painting and cartography. Maps documenting prominent geographical features (such as mountains, rivers or settlements) have been found in Stone Age cave paintings, incisions on clay tablets, and diagrams etched onto rock, tusks or bone – suggesting that the human impulse to visually record our immediate environment extends back to prehistoric times. According to Levi-Strauss, by seeming to simplify the landscape through a reduction in scale, these ‘manmade miniatures’ are not just “pleasing projections or passive homologues” of the scenes they represent – “they constitute a real experiment with it”.[vii] In this way, each artwork created by Ballinglen fellows is a unique artefact that retains the history of its own making – whether recording stylistic innovations, fleeting ambient conditions, or the memorialisation of the built environment for posterity.

At the conclusion of their residency, each artist gifts an artwork to the Ballinglen Permanent Collection, which currently comprises over 850 artworks. Amassed over a 30-year period, the collection forms an important durational record of artistic experience within the locality. This living archive is effectively a microcosm of North Mayo, spanning multiple vantagepoints, mediums and timeframes. It constitutes a unique and special legacy for the region, precisely because it contains and preserves all manner of conceptual, environmental and epistemological processes, directly arising out of immersion in the surrounding landscape.

The Ballinglen Museum of Art is a custom-built, contemporary gallery space, adjacent to the main building, which was officially opened last year to suitably house and exhibit the permanent collection, while also accommodating a new education centre, print gallery and meeting rooms. Presented this winter is the group exhibition, ‘The Way That We Went’ – a title which plays on an early-twentieth-century guidebook by Robert Lloyd Praeger[viii], an Irish naturalist and botanist who walked around Ireland “with reverent feet”, rejecting motor transportation, while “stopping often, watching closely, listening carefully.”[ix]

Curated by Anne Mullee, the exhibition is thematically assembled around contemporary interpretations of landscape that extend beyond idyllic, romanticised or clichéd touristic frameworks, to reimagine rural mythologies. A two-pronged curatorial process has brought together a robust selection of artists previously unconnected to Ballinglen [x], whose enigmatic artworks will undoubtedly find a receptive audience there. These are presented alongside selected works from the permanent collection by past fellows of Ballinglen[xi], who have also been invited to show an additional new or existing work, many of which have been obtained on loan from other private or public collections.

Collectively the selected artworks capture the realities of rural life, from the ritualistic to the ad-hoc, whether illustrating agricultural produce (such as Comghall Casey’s trussed shoulder of lamb), the occasional loneliness felt in remote locations (as chronicled in Mollie Douthit’s studies of solitary chairs) or distant woodland scenes, found in Kathy Tynan and Cecilia Danell’s portrayals of remote forests in Ireland and Sweden respectively. The sparse simplicity of monochromatic drawings and prints – such as Donal Teskey’s nimble drypoint etching or Pat Harris’s moody charcoal study – offer quiet counterpoints to the exhibition’s more dramatic painterly moments, found in Nick Miller’s expressive depiction of Benwee Head, Martin Gale’s brooding scenes of rural habitation, or Eithne Jordan’s pensive study of a remote Mayo bungalow. Also presented is one of the collection’s only moving image works, created during lockdown by Ballycastle-based artist, Nuala Clarke, whose abstract dreamscapes recount colour experiments by seventeenth-century Irish alchemist, Robert Boyle. A kaleidoscopic colour palette is also observed in Peter Burns’ fantastical landscape, while Selma Makela’s night sky, illuminated with cosmic lights, shows the magic of the natural world, reviving landscape as the site of the sublime.

Joanne Laws is an art writer and editor based in the west of Ireland.

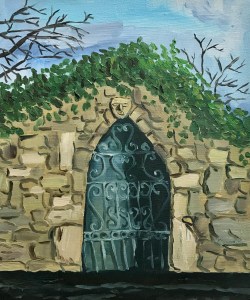

Featured Image: Kathy Tynan, Watching from the sky, 2020, oil on canvas, 30x 25cm; image courtesy of the artist and Ballinglen Foundation.

[i] Robert Lloyd Praeger, ‘Irish topographical Botany’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 7, Series 3, 1901, pp 1 – 140.

[ii] The Céide Fields was originally discovered in the 1930s by schoolteacher, Patrick Caulfield, who, while cutting turf, noticed organised piles of rocks that were located below the blanket bog, suggesting an ancient origin. Patrick’s son, Seamus, later studied archaeology and led excavations of the site from 1969 onward.

[iii] Megan Harlan, ‘A Pompeii in Slow Motion’, New York Times, 8 July 2001.

[iv] Seamus Heaney, Belderg, 1975. The poem reportedly accompanied a letter from Heaney to Patrick Caulfield, after Heaney’s visit to The Céide Fields in 1974.

[v] Glib (Historical, Irish) – A thick mass of curly hair, worn down over the eyes.

[vi] Tim Robinson, Interim Reports (Galway: Folding Landscapes, 1995) p 76.

[vii] Claude Levi-Strauss, The Savage Mind, Trans. George Weidenfield and Nicholson Ltd (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962) p 63.

[viii] Robert Lloyd Praeger was an Irish naturalist, writer and librarian who worked in the National Library of Ireland in Dublin from 1893 to 1923. He co-founded and edited the Irish Naturalist and wrote extensively on the natural history of Ireland.

[ix] Robert Lloyd Praeger, The Way That I Went (Dublin: Hodges & Figgis & Co, 1937).

[x] Exhibiting artists (new to Ballinglen): Peter Burns, Éanna Byrt, Cecilia Dannell, Kaye Maahs, Selma Makela, Matthew Mitchell (TBC), Will O’Kane, Joe Scullion (TBC) and Kathy Tynan.

[xi] Exhibiting artists (Ballinglen past fellows): Comhghall Casey, Nuala Clarke, Mollie Douthit, Martin Gale, Patrick Harris, Eithne Jordan, Nick Miller, Geraldine O’Reilly and Donald Teskey.